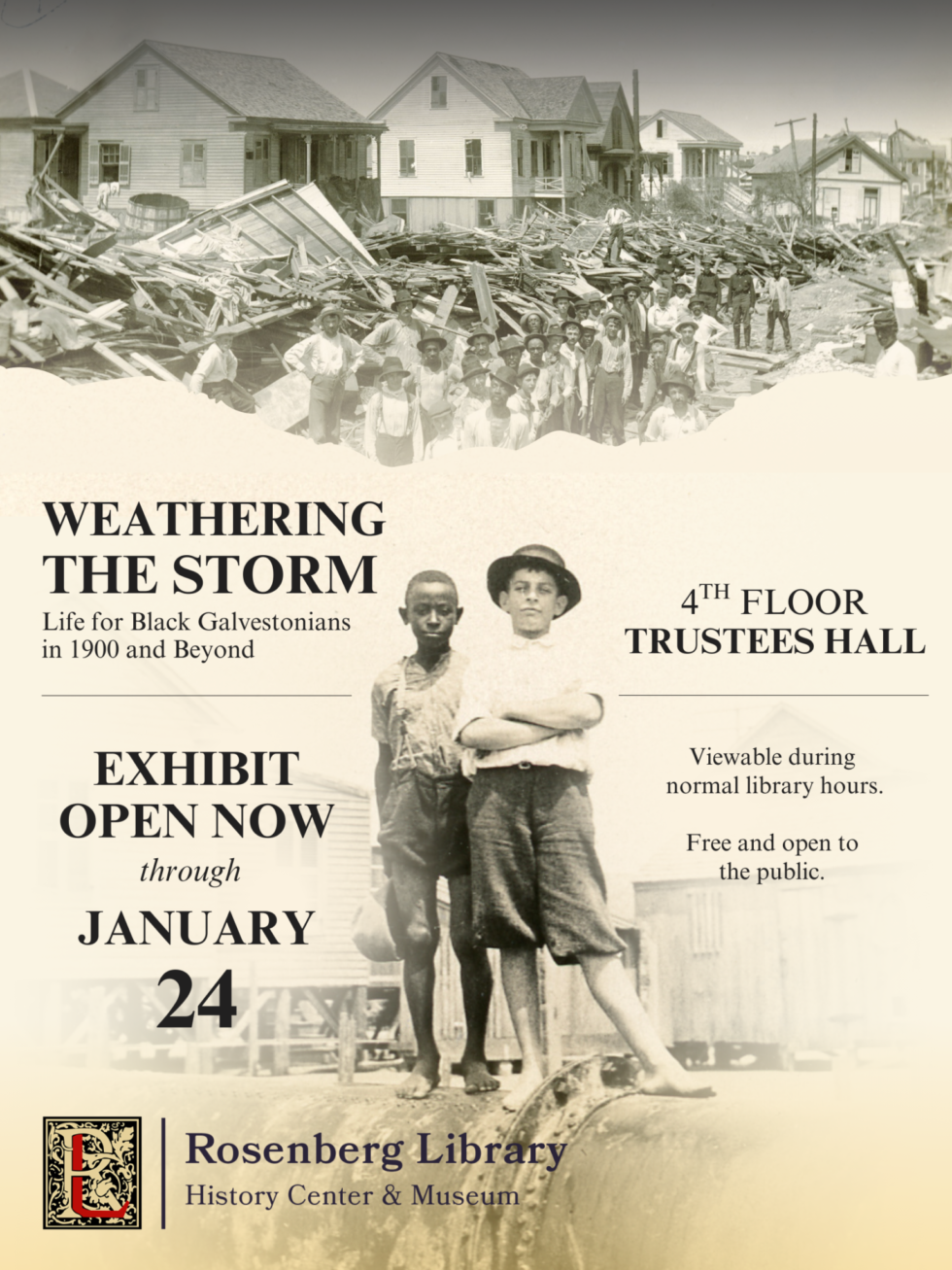

Join us in person or online to explore the history of the 1900 Storm and its impact on the Black community in Galveston. See photographs, artifacts, and art and learn about some of the incredible heroes of this era.

The exhibit is located on the 4th floor in Trustees Hall. It can be viewed during regular library hours, 9:00 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. Monday through Saturday. No appointment needed. For more information, please contact the Museum Curator at 409.763.8854 Ext. 125 or at museum@rosenberg-library.org.

For press inquiries, please contact the Communications Coordinator at 409.763.8854 ext. 144 or Communications@Rosenberg-Library.org.

2025 marks the 160th anniversary of Juneteenth and the 125th anniversary of the 1900 Storm. Both events have shaped Galveston history and made the island what it is today. Natural disasters often highlight disparities in society, and the 1900 Storm was no different. The Storm devastated Galveston, causing immense damage to churches, schools, and homes and greatly impacting Black communities on the island. In the Storm’s aftermath, Black people were maligned and mischaracterized by news coverage of the recovery efforts, paving the way for Jim Crow laws to be passed in Galveston and stripping away the progress that had been made during Reconstruction. The 1900 Storm irrevocably changed the fabric of Galveston society and especially the Black community, with many Black people leaving Galveston permanently.

However, despite facing segregation and discrimination in all aspects of life, Black Galvestonians demonstrated incredible resilience, rebuilding their institutions and continuing the fight for equal rights. Though the full promise of Juneteenth and absolute equality has yet to be fulfilled, the convergence of these two important anniversaries allows us a chance to reflect on the incredible stories within an often-overlooked part of Galveston history.

Read about the lives of some notable Black Galvestonians below:

Notable Figures in Galveston Education

Notable Figures in Galveston Churches & Cemeteries

Notable Figures in Galveston Labor & Politics

Notable Figures in Galveston Housing

George T. Ruby (1840 – 1882)

George T. Ruby was born in New York City in 1841 and grew up in Portland, Maine. His first job was working as a newspaper correspondent in Haiti for the Boston newspaper The Pine and The Palm. He returned to the United States in 1864 and began working for the Freedman’s Bureau as an elementary school principal in New Orleans. Ruby helped establish many schools throughout Louisiana.

Ruby then moved to Galveston in 1866 to continue his work for the Freedman’s Bureau. He quickly joined the Union League, an organization dedicated to mobilizing Black people to vote in support of the Republican Party. Ruby’s influence in the League allowed him to successfully run for the Constitutional Convention of 1868, making him one of the first Black men elected to public office in Texas. Later, he was elected as a state senator to serve in the 12th legislature in 1870 and the 13th legislature in 1873. Ruby used his position to ensure the protection of basic civil rights for Black people and to strengthen their position within the political landscape.

Ruby was also influential in the Galveston labor movement. He was appointed as a customs officer in 1869 and was elected president of the Texas Colored Labor Convention that same year. He also helped black workers gain jobs at the Galveston docks after 1870.

After the Democrat party regained power in 1874, Ruby moved back to New Orleans, where he worked as an editor for several different newspapers until his death in 1882.

J.R. Gibson (ca. 1865-1948)

Professor John Rufus Gibson was born and raised in Virginia. After graduating from Wilberforce University in Ohio, Gibson moved to Galveston in 1883 to begin teaching in the city school system. After only three years, he was promoted to principal of East District School, and two years after that, in 1888, he was promoted again to principal of Central High School. Gibson was widely respected as a community leader and worked closely with Clara Barton after the 1900 Storm to provide relief to Storm survivors. Barton entrusted Gibson directly with money earmarked for Black Galvestonians to ensure aid was distributed fairly. Gibson was recognized for his humanitarian efforts in 1901 when President McKinley appointed him consul general to Liberia.

Gibson continued to pursue higher education, attending the University of Chicago and earning a master’s degree from Wilberforce University in 1901. In 1905, Professor Gibson was hired as manager of the Rosenberg Library Colored Branch in addition to his duties as principal of Central High School. Under Gibson’s leadership, both the library and school expanded to provide a wealth of opportunities for Black students. In 1935, a petition to honor Gibson by changing the name of Central High School to Gibson High School was presented to the Galveston School Board with over 200 signatures. The board deferred the request, and Gibson retired a year later in 1936. Gibson continued to serve as an active member of Reedy Chapel A.M.E. Church and the Colored Teachers State Association until his death in 1948.

Lillian Davis (1897-1955)

Lillian Davis was born in Galveston on January 27, 1897. She graduated from Central High School in 1916 and was hired as the assistant librarian at the Rosenberg Library Colored Branch in 1918. Davis worked with the head librarian and principal of Central High School, John R. Gibson, to build a collection of books by Black authors and scholars.

Davis was promoted to Head Librarian in 1928 and created many popular programs like the Book Lovers’ Club and the annual celebrations of Negro History Week (now Black History Month). In 1951, the Rosenberg Library Board of Directors awarded Davis with a check for $100 in recognition of 33 years of employment with the organization—at the time, she was the longest-serving member of the Rosenberg Library staff.

Sadly, Lillian Davis died of heart failure in November 1955, less than a year after the opening of the new Colored Branch library. Members of her Book Lovers’ Club served as honorary pall bearers at her funeral. Davis is buried at Memorial Cemetery in Galveston.

Reverend Ralph A. Scull (1860-1949)

Reverend Ralph Albert Scull was born in Port Bolivar, Texas, in 1860 to Horace and Emily Scull. At the end of the Civil War, his family moved to Galveston. Scull was taught by several private tutors growing up, including the daughter of the first pastor of Reedy Chapel A.M.E. Church. Scull attended college in Ohio and Indiana and returned to Galveston to teach in 1883. He was the first Black man to be raised and educated in Galveston, obtain higher education, and return to teach in Galveston. Scull taught at both the East and West District Schools, eventually serving as the principal of West District School. He served in the local public school system for 52 years and retired from teaching in 1935.

Scull was also an active member and class leader at Reedy Chapel A.M.E. for many years. He became an ordained minister in 1919 and established St. Andrews Missionary Church in Galveston using his own money. He also pastored in Double Bayou, Dickinson, and Texas City. Reverend Scull passed away in 1949. In his will, he requested that St. Andrews be renamed to Scull Chapel.

Jessie McGuire Dent (1892-1948)

Jessie May McGuire was born in Galveston in 1892. She graduated from Central High School in 1909 and attended Howard University in Washington, D.C., where she was a founding member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority. After completing her college degree, McGuire returned to Galveston and was hired to teach English and Latin at Central High School in 1913. In 1924, she married Galveston attorney Thomas Dent. They had one son, Thomas Dent, Jr., born in 1929. The couple divorced in 1938, and tragically, Thomas Dent, Jr., died two years later.

Despite her devastating loss, McGuire Dent served as the Dean of Girls for Central High and maintained an active leadership role in several organizations, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Colored Teachers State Association. After teaching at Central High School for 30 years, McGuire Dent petitioned to obtain equal pay for Black teachers and won her lawsuit against the Galveston School Board of Trustees in 1943.

McGuire Dent passed away in 1948. In 1999, the city of Galveston recognized her accomplishments by dedicating the McGuire-Dent Recreation Center at Menard Park, located on 2222 28th St., half a block away from her home.

Herman Barnett (1926-1973)

Herman Aladdin Barnett III was born in Austin, Texas in 1926. After graduating from Phillis Wheatley High School in Austin in 1943, Barnett served as a fighter pilot in the 332nd Fighter Group in the United States Army Air Force for two years. Barnett then pursued higher education at Samuel Huston College, where he graduated with honors in 1949.

Barnett became the first Black man to attend and graduate from the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. This achievement was hard won: though Barnett had been accepted to Black medical schools, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) encouraged Barnett to apply to UTMB and promised to fund a lawsuit if he was not admitted. In response, the State of Texas enrolled Barnett at Texas Southern University but allowed him to attend medical classes at UTMB. However, the Department of Veterans Affairs, which paid Barnett’s tuition through the G.I. Bill, refused to recognize this arrangement, and Barnett was officially enrolled at UTMB. Barnett faced discrimination and racial prejudice throughout his time at medical school, even surviving a beating by a Galveston County sheriff’s deputy.

Barnett graduated cum laude from UTMB and was licensed to practice medicine in 1953. He interned in the University of Texas hospital system and completed a four-year residency there, specializing in trauma surgery. Over the course of his career, Barnett was affiliated with many hospitals and served as chief of surgery at St. Elizabeth’s, Riverside General, and Lockwood.

Barnett continued breaking barriers by becoming the first Black man to be appointed to the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners in 1968. He was also the first Black man to be elected president of the Houston Independent School District Board in 1973. Barnett received numerous fellowships and awards throughout his career and was very active in several professional organizations such as the Texas Medical Association and Harris County Medical Society.

In his spare time, Barnett continued to fly airplanes and even established a local aviators’ group, the Bronze Eagle Flying Club, in 1968. Unfortunately, he died in a plane crash in 1973 when his private airplane was caught up in unexpected crosswinds. To honor his legacy, his friends created the Herman Barnett Memorial Award for medical students, and UTMB established the Herman A. Barnett Distinguished Endowed Professorship in Microbiology and Immunology. UTMB also posthumously awarded him the Ashbel Smith Award, the school’s highest honor, and the Houston Independent School District named Herman A. Barnett stadium in his honor.

Reverend Perrie Joy Jackson (1936-2012)

Reverend Perrie Joy Jackson was born in Galveston in 1936. She attended Central High School, graduating as Valedictorian in 1953. Jackson went on to become the first Black woman to attend and graduate from Perkins School of Theology. In 1957, she continued making history as the first woman granted to preach in the Texas Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church.

In 1962, Rev. Jackson became the first Black person to be ordained as a deacon in the Texas Conference and became the first elder ordained in 1967. She preached and pastored at churches all over Galveston County, particularly at Wesley Tabernacle United Methodist Church in Galveston, where she was the longest tenured pastor in the church’s history. Additionally, she served as Founding Pastor at First UMC Prairie View and was a former educator and member of the Galveston Retired Teachers.

In 2005, Rev. Jackson retired after 43 years of service as a Methodist pastor, more than any woman to date in the Texas Conference’s history. Rev. Jackson continued to be an active member at Wesley Tabernacle, teaching children’s Sunday School classes and singing in the choir. Rev. Jackson passed away at age 76 on December 1, 2012 and was laid to rest in Lakeview Cemetery.

Reverend James B. Thomas (1924-2007)

Reverend James B. Thomas was born in Galveston in 1924. After graduating from Central High School in 1943, he went into the U.S. Navy as a machinist’s mate – an engineer responsible for maintaining and repairing ship machinery – and served in the Pacific during WWII. After his discharge from the Navy, Thomas was hired by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway where he was relegated to a job as a laborer and, because of his race, was denied the promotion he earned and deserved. Seeking other employment, Thomas took a Post Office examination in 1949 and passed, landing him a position as Galveston's first black letter carrier. In 1952, he became the city's first black postal clerk.

Thomas graduated from the Baptist Institute of Theology and Christian Doctrine in 1966 and served as pastor of the Market Street Missionary Baptist Church from 1978 to 2002. After his election as president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1979, he lobbied successfully for a bill that designated Juneteenth as an official Texas state holiday led the effort to revive annual Juneteenth celebrations in Galveston. Rev. Thomas was elected to the City Council in 1985, becoming the third black City Council member in Galveston's history.

On March 16, 2007, Rev. Thomas passed away at age 82.

“Uncle” Newton Taylor (c. 1828-1905)

“Uncle” Newton Taylor (also known as “Old Doc”) was born around 1828 in Mississippi, likely to an enslaved family. He later came to Galveston and was hired by Reverend Stephen Bird of Trinity Episcopal Church to be the church's organ blower and grave digger. Taylor was an active member of Holy Rosary Catholic Church, the first Black Catholic church in Texas, and was well known in the community. He is believed to have dug hundreds of graves for deceased Galvestonians and always attended their services as a mourner. Taylor died in 1905 and is buried in an unmarked plot at the Old Catholic Cemetery on Avenue K.

W.K. Hebert (1888-1958)

William Kendal Hebert was born in Beaumont, Texas in 1888. He was the only male in the first graduating class of Beaumont Colored High School. After earning a degree from Prairie View State Normal and Industrial College, Hebert enrolled at the Cincinnati College of Embalming to earn his embalming license. In 1916, Hebert and a Galveston associate, C.S. Willis, opened Willis & Hebert Embalmers and Funeral Directors at 2401 Avenue E.

During World War I, Hebert left Galveston to join the U.S. Army. Willis died a short time later, and their joint funeral business closed. Upon his honorable discharge from the military in 1919, Hebert opened W.K. Hebert & Company at 610 24th Street.

In 1930, the business moved to 2827 Avenue M ½, where it continued to operate for more than 50 years. When Hebert died in 1958, his brother Nando assumed ownership of the company and continued its operations until his own death in 1987.

BJ Strode (1908-1948)

Bethel Julius “BJ” Strode was born in Patterson, Louisiana in 1908. His family moved to Galveston in the late 1910s or early 1920s. Strode graduated from Central High School in 1926 and married Galveston native Oberian Banks at Reedy Chapel A.M.E. in 1934. Their large wedding was covered in the Galveston Daily News as a notable event.

Strode worked as a mortician and established his own business, Strode Funeral Home. In World War II he served as a flight instructor on the Tuskegee 99th Squadron. At the Tuskegee Institute, Strode met his second wife, Celestine Shannon, with whom he had two children.

Strode was so successful as a businessman that he owned his own airplane. Unfortunately, on January 1, 1948, he died while piloting that plane on a flight from Galveston to New Orleans, along with his mother Estella and the pastor of Wesley Tabernacle United Methodist Church, Reverend W.H. Hightower. Their bodies, as well as the plane, were never recovered, and they were declared officially dead in 1950.

Norris Wright Cuney (1846-1898)

Galveston politician and civil rights leader Norris Wright Cuney (1846 – 1897) became a source of inspiration for newly emancipated African Americans in Texas in the years following the Civil War. He fought to secure economic, political, and educational equality for all citizens, and he achieved great personal success in spite the racial prejudice he faced throughout his life.

Cuney was born into slavery on Sunnyside plantation near Hempstead, Texas in 1846. His father, Philip Minor Cuney, was a state senator and among the wealthiest planters in the state. Among the 105 slaves on his 2,000 acre property was Adeline Stuart, with whom Philip Cuney fathered eight children between 1839 and 1860.

During the 1850s, Philip Cuney manumitted Adeline and all of their children. Their two oldest sons were sent to Pennsylvania for formal education. In 1859, thirteen-year-old Norris Wright Cuney left Texas to join his two older brothers at George B. Vashon’s Wylie Street School in Pittsburgh. However, the Civil War brought an end to the boys’ schooling. Cuney found work on steamboats that traversed the Mississippi River.

Cuney eventually returned to Texas and settled in Galveston. He married Adelina Dowdie in 1871. Like her husband, Dowdie’s father was a white planter while her mother was a slave of mixed race. Adeline Dowdie worked as a teacher in Galveston’s public schools and both she and her husband were devoted to improving educational opportunities for African Americans during Reconstruction. The Cuneys had two children—a daughter, Maud, and a son, Lloyd Garrison.

In 1873, Cuney was appointed an inspector of customs at the port of Galveston. Following in his father’s political footsteps, Cuney became a leader in the local Republican Party and was eventually appointed secretary of the state’s Republican Executive Committee. On a local level, Cuney also worked to improve the conditions and expand the opportunities available to African-American dockworkers. He organized the Screwman’s Benevolent Association in an effort to ensure fair pay for black longshoreman.

In 1883, Cuney became the first African American elected as an alderman for the City of Galveston. Representing the 12th Ward—a majority white district on the city’s East End—Cuney worked to promote equality in the city’s public school system. When his motion to create a single, integrated public high school was voted down by fellow council members, he secured funding to establish Central High School, the state’s first high school for African American students.

President Benjamin Harrison appointed Cuney Collector of Customs for the Port of Galveston in 1889, making him one of the most influential people of color in the American South. Cuney was the first Grand Master of the Prince Hall Masons in Texas and held memberships to the Knights of Pythias and the Odd Fellows. He died in 1898 and was buried alongside his wife at Lake View Cemetery in Galveston.

In 1937, the City of Galveston established Wright Cuney Park in his honor. Today, the site is operated as the Wright Cuney Recreation Center at 718 41st Street.

Doc Hamilton (1870-1939)

D.H. “Doc” Hamilton was president of the International Longshoremen’s Association Local No. 851 in Galveston from 1930 through 1937. He is credited with establishing Local 851 as an important force in the Galveston ILA, which had several chapters at the time. He was also the first Black man to be elected to the executive board of the South Atlantic and Gulf Coast District of the ILA, where he served as vice president. Hamilton was also elected as vice president on the International Executive Board. He died in 1939; his funeral was held at the City Auditorium and was the only funeral ever held in that building.

Gus Allen (1905-1988)

Andrew Augustus “Gus” Allen was born in Leesville, Louisiana in 1905 and moved to Galveston in 1922. He worked as a shoe shiner in the lobby of the Hotel Galvez but quickly sought better work opportunities elsewhere. Allen moved first to Houston, then to Kansas City, Chicago, Detroit, and New York, before ending up in Biloxi, Mississippi, where he worked for several years as a waiter in an upscale restaurant. Allen saved up over $300 from his paychecks and returned to Galveston in 1930. He rented his uncle’s boardinghouse and café on 2704 Church Street and opened the Dreamland Café, later changing the name to Gus Allen’s Café.

Allen continued to expand his business ventures, acquiring a boardinghouse next to the café as well as a hotel, a barbershop, and many other businesses serving Black customers. He also supported and invested in other Black business owners like Nelson “Honey” Brown, who opened Honey’s Barbecue, and Albert Fease, who opened the Jambalaya Café, both in Allen’s buildings.

Allen was not only influential as an entrepreneur, but also as a humanitarian. Allen fundraised for the survivors of the Texas City Disaster in 1947 and supported the civil rights movement in Galveston, particularly during the lunch counter sit-ins of 1960. Allen passed away in 1988 and was interred at Memorial Cemetery.

T.D. Armstrong (1907-1972)

Thomas Deboy “T.D.” Armstrong was born in Meeker, Louisiana in 1907. He attended Tuskegee Institute and graduated from Prairie View A&M with a bachelor’s degree in 1929. Armstrong taught school in Louisiana and Port Arthur before moving to Galveston in 1938 to manage the Strode Funeral Home.

Armstrong quickly became a successful and well-known businessman on the island, acquiring another funeral home, a drug store, motel, barber shop, and real estate firm. He was also president of Tyler Life Insurance Company. His personal wealth was noted in several articles in Ebony Magazine and other publications, and he was included in Ebony’s May 1962 list of “America’s 100 Richest Negroes.”

Armstrong was very active in the Galveston community, serving on numerous city committees. In 1961, he became the first Black man to be elected to Galveston’s city council since Norris Wright Cuney in 1883. Armstrong was also an active Democrat and served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1964 and 1968. He died in Galveston in 1972.

Kelton D. Sams (1943-)

Kelton D. Sams Jr. was born in Galveston and attended Central High School. During the spring break of his junior year, he and fellow students led a sit-in at multiple diners and restaurants, leading to the desegregation of restaurants in Galveston. Sams also led a sit-in that resulted in the desegregation of Stewart Beach.

After graduating from Central High in 1961, Sams attended Texas Southern University, where he earned a B.A. in Economics in 1965. Sams continued his work as a social activist, leading peaceful protest movements to desegregate movie theaters and encourage black voter registration in Houston. He was also involved in Houston's War on Poverty programs through the Harris County Community Action Agency, where he led several initiatives.

Sams worked for the City of Houston for many years as a contractor and Construction Project manager until his retirement. He is a also real estate broker, ordained minister in the United Church of Christ, and owner of multiple fast-food businesses. In 2015, he became a National Best-Selling Author when he published his autobiography Growing Up In Galveston, Texas: Walls Came Tumbling Down.

Horace Scull (c.1830-1895)

Horace Scull was born into slavery around 1830 in Port Bolivar, where he lived until the end of the Civil War. Afterwards, he moved to Galveston with his wife, Emily, and son, Ralph Albert Scull. His daughter, Clara Emma Scull, was born just a year later. Scull was a skilled carpenter and was instrumental in building new homes, churches, and schools for other newly emancipated Black people in Galveston. His name is included on one of the cornerstones for Reedy Chapel A.M.E. Church. Scull worked for J.S. Sauters and B.R. Davis furniture stores before opening his own business, which served the leading families of Galveston until his death in 1895. Scull was buried in Oleander Cemetery.

Clara Scull (1866-1935)

Clara Emma Scull was born in Galveston in 1866 to Horace and Emily Scull. Scull attended school in Galveston and later graduated from Tillotson College in Austin, TX. She returned to Galveston in the 1880s to teach at the East District School and later at Central High School. At the time, Scull and her brother, Ralph Albert Scull, were the only Black public school teachers in Galveston who were born on the island.

Scull was the National Grand Secretary and “National Princess” of the National Grand Temple of the Sisters of the Mysterious Ten, a Black women’s organization that cared for sick, dying, and disabled people. After the 1900 Storm, Clara appealed to the N.G.T.S.M.T. for aid for Black survivors. Her home was one of those destroyed in the Storm and rebuilt.

John Arthur "Jack" Johnson (1878-1946)

Nicknamed “The Galveston Giant,” Jack Johnson was the first Black world heavyweight boxing champion, from 1908-1915. Johnson was born in Galveston in 1878, and first learned to box when he traveled to Dallas and New York to find work as a young man. In 1898, Johnson returned to Galveston and made his professional debut, winning a match against Charley Brooks.

Johnson won the titles of World Colored Heavyweight Champion in 1903 and World Heavyweight Champion in 1908. Though Johnson faced racist press throughout his career, his defeat of Tommy Burns, a white man, for world heavyweight champion spurred extreme racial animosity. In 1910, former undefeated heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries came out of retirement to challenge Johnson. Johnson successfully defended his title in the “Fight of the Century,” knocking Jeffries down twice for the first time in his career. Race riots broke out after the fight in more than 25 states and 50 cities, killing at least twenty people and injuring hundreds more.

Johnson continued to face discrimination. After his marriage to Lucille Cameron, a white woman, he was arrested for violating the Mann Act, which outlawed the transportation of women across state lines for “immoral purposes.” While the Mann Act was originally intended to prevent prostitution and human trafficking, it had racist undertones and was often used to prosecute interracial relationships.

Johnson was sentenced to a year in prison, which he served from 1920-1921. He died in a car crash in 1946 and was posthumously pardoned by President Donald Trump in 2018.