The Rosenberg Library Museum presented a model train of the Galveston Flyer as the December 2011 Treasure of the Month. This brass replica was made in Japan by G. S. B. Rail Ltd. and purchased by the Rosenberg Library in June 2010. Although it has yet to be painted or adorned with decals, it still serves as a striking reminder of the efficient public transportation that once connected Galveston and Houston.

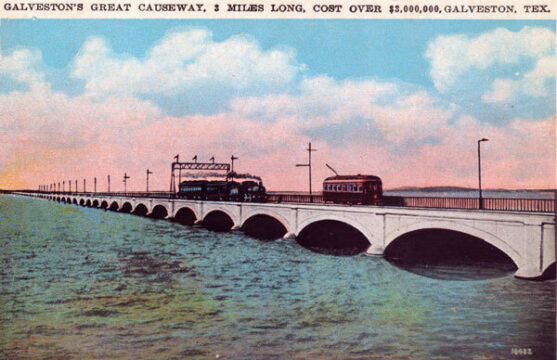

The Galveston-Houston Electric Railway Company (or as most people called it… “The Interurban”) operated between the two cities from December 5, 1911 to October 31, 1936. The company formed in 1905 when local businessmen hired Boston-based Stone & Webster Engineering Corp. to plan the project. Stone & Webster pledged $500,000 to subsidize the cost of building the Causeway which ended up totaling $2 million. The firm chose a direct cross-country route (as opposed to following the coast, as was originally proposed) which passed through Genoa, Webster, League City, Dickinson, and La Marque. Although the tracks typically missed city centers, the Interurban helped develop these towns and drove up land prices. Construction started March 28, 1910, and the last spike was driven into the ground on October 19, 1911.

The Interurban averaged 1 million passengers a year during its twenty-five year service. A one-way ticket cost $1.25; a round trip was $2. To entice riders the Interurban offered specials for weekend trips, hunters, dog-track-goers, and policemen. The Galveston-Houston Electric Railway Company also stirred interest with a monthly magazine called The Tangent. It chronicled interesting tales from employees and patrons about the line and became so popular that a number of people subscribed to it. Passengers could bring their dogs on board, but “lap dogs had to be kept on the passengers lap.” Hunters could check their guns, and passengers were allowed to check luggage of up to 150 pounds. In addition to passengers, the Interurban also carried freight including – agricultural goods, dairy, poultry, oil, and beer.

The Galveston-Houston Electric Railway Company had very high standards for its employees. Motormen and conductors were carefully selected and underwent specialized training. Many of the company’s policies, such as refraining from drinking, swearing, smoking, or gambling on duty, might seem like common sense but represented the cutting edge of professionalism at the time. Workers’ watches were inspected regularly to ensure that everyone kept the same time, and the cars had headlights that could illuminate up to two-thirds of a mile. Safety was of the highest priority for the line as well. Master mechanics regularly checked cars and had to approve them before they could leave the barns to return to service.

The Galveston Flyer won the Electric Traction magazine annual speed award in 1925 and 1926. It covered the 50.47 miles from downtown Houston to Galveston in an hour and fifteen minutes and had a top speed of sixty miles per hour. Geography played an important part in its speed and allowed for a very fast trip: thirty-four miles of track were completely straight and the maximum grade it encountered was a short 3% grade bridge. The Interurban was powered by two 1500-kilowatt, 2300-volt, 60-cycle alternators, each driven by a horizontal Curtiss turbine. Its main power plant on Clear Creek burned coal or oil and delivered 600 volts of electricity to the trolley lines.

The Interurban was able to weather the storm of 1915 (although the Causeway was damaged causing the loss of service for a week) and the Great Depression, but by the mid 1920s ridership began to decline. Ultimately the Interurban fell victim to a newer, more personalized, form of transportation: the automobile. The Galveston-Houston Electric Railway Company invested heavily in busses, and much of the railroad’s right-of-way property was rich in oil. On Halloween day 1936, the Galveston Daily News modestly noted: “Galveston’s historic interurban line… gave way last night to the march of time, and ceased operation after 25 years of almost continuous service.”

The replica on display is a ‘Standard’ model similar to the ten cars purchased in 1911 from the Cincinnati Car Company by the Galveston-Houston Electric Railway. The ‘Standard’ weighed 72,000 pounds, was 52 feet long, nine feet wide, and thirteen feet high. They were originally painted Pullman green with gold lining and lettering, and later the named cars (such as the Galveston Flyer or the Houston Rocket) were painted blue with dark blue roofs, white window posts, red window frames and doors, and white headlights. On the side of the cars were white oval bluebird emblems. The Standard had two compartments and could sit 54 passengers. The interior had beautiful Honduras Mahogany, English agasote, bronze trim and luggage racks, wool carpet, and silk curtains. Cars also had a bathroom in the rear and a water cooler with paper cups for patrons to quench their thirst.

While the Interurban has been out of service for over seventy years, its legacy still lives on. It cemented Galveston as an affordable get-away for people in the surrounding region, helped develop many of the cities along its route, and forged a bond between Galveston and Houston that lasts to this day. Additional information on the Interurban, including photographs and postcards, can be found at the Galveston and Texas History Center at the Rosenberg Library or Galveston-Houston Electric Railway: Interurbans Special No. 22 by Herb Woods.