During the month of October, Rosenberg Library exhibited a small collection of items related to Kirwin High School, an all-boys parochial school which operated in Galveston from 1927 – 1968. Included in the display was a band uniform from the 1950s, vintage photos, and other souvenirs from the school’s history. O’Connell College Preparatory School now operates in the former Kirwin High building on 23rd Street.

Brothers of Christian Schools

Kirwin High School was managed by the Brothers of Christian Schools (also known as the Christian Brothers), a Catholic teaching order established in France during the 17th century. The Christian Brothers first came to America in 1845 to open a school in Baltimore. Their success in that city and in New Orleans led to their recruitment by Galveston Bishop John Mary Odin in 1861. During the turbulent Civil War, the brothers operated St. Mary’s University, a Catholic high school for boys. In 1867, a yellow fever outbreak caused the deaths of many Galveston residents including several of the Christian Brothers. With an insufficient teaching faculty, the order was forced to abandon its post on the island. For many years, the city lacked a Catholic high school for boys.

In 1927, the diocese purchased the residence of the late Col. William L. Moody, Sr. on Tremont (23rd) Street and converted it into a high school for boys. It was named in memory of Msgr. James M. Kirwin who had died the year before. Dominican and Ursuline nuns taught at Kirwin High School until 1931 when the Christian Brothers returned to Galveston to assume operations. By 1942, the school was in need of a more modern facility, and a new building was constructed on the same site at 23rd Street between Avenues M and N.

In March 1961, a groundbreaking ceremony was held for a new addition to the building along the eastern side. Designed by architect Raymond Rapp, it provided space for a new gymnasium and cafetorium. Seven years later, Galveston’s two all-girls academies — Dominican and Ursuline — merged with Kirwin High School to form O’Connell College Consolidated High School (later renamed O’Connell College Preparatory School), a co-educational Catholic high school which today continues the long tradition of education for young men and women on the island.

The Namesake of Kirwin High School

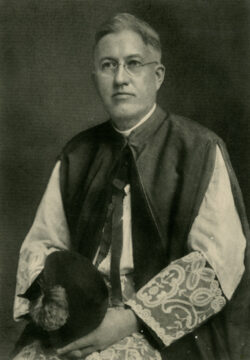

Kirwin High School was named for Msgr. James Martin Kirwin, an Ohio native who came to Galveston as a young priest at St. Mary’s Cathedral in 1896. He assisted Galveston’s infirm during the yellow fever outbreak of 1897, and then served as a U.S. Army chaplain during the Spanish-American War. Kirwin was a leading figure in the rebuilding of Galveston after the Great Storm of 1900. He created the Committee for Public Safety which fed the hungry, cared for the injured, and buried the dead after the devastating event which claimed thousands of lives. In 1901, the Galveston Fire Department awarded Kirwin a gold medal for risking his life to rescue people from a burning building — a valiant effort which left him with permanent sight damage.

Along with other religious leaders, Msgr. Kirwin thwarted efforts by the Ku Klux Klan to rally in Galveston and worked with the Home Protective League to move saloons out of residential areas. He also served as a mediator during the 1907 Southern Pacific dock workers strike. In addition to his community involvement, Kirwin worked tirelessly on behalf of the Catholic ministry. He was an effective fundraiser and financial manager, charged with overseeing the island’s Catholic schools and orphanage as well as its church buildings.

The entire city mourned the unexpected death of Msgr. Kirwin when he died in his sleep in January 1926. He was found unresponsive in the St. Mary’s rectory after suffering a heart attack at age 53.

Thousands of islanders paid their last respects during a four-day period in which Msgr. Kirwin’s body lay in state at the cathedral. Reports in the January 29 edition of the Galveston Daily News described his funeral procession as “a seething melting pot in which creed and color, rank and station, were forgotten” and noted that it was “one of the most moving … ever seen in Galveston.”